Walleye in a broth made from braised greens is one of the courses on Owamni’s new tasting menu.

Sean Sherman is putting a fine-dining spin on Indigenous cuisine at the Minneapolis restaurant, and in the process is setting up his nonprofit — and Native producers — for success.

By Sharyn Jackson Star Tribune | JANUARY 11, 2024 — 7:00AM

It’s a long road from a food truck to a 13-course tasting menu, but that’s exactly the road Sean Sherman is taking.

The star chef and co-founder of the critically acclaimed Owamni — which originated as the Tatanka food truck back in 2015 — is brightening the slowest restaurant season with a major pivot.

Through Valentine’s Day, lunch is canceled and the a la carte menu is no more. As for walk-ins at the notoriously booked-up James Beard Award-winning restaurant? Forget about it.

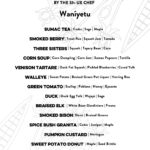

Instead, look for the new Waníyetu tasting menu. As always, Owamni is showcasing Indigenous, North American cuisine. But this limited-time tasting takes a more elevated, boundary-pushing approach to ingredients like squash, bison, venison and sumac, than returning guests might be used to. Those staples become squash jam on a one-bite blue corn tostada, smoked bison with braised greens, venison tartare, and sumac tea.

Tickets, which must be reserved in advance, are $175.

Sherman suspects you might be wincing about now.

“It’s really ambitious,” he said while introducing the menu at a recent sneak peek. “If we were in Chicago or New York or L.A. or San Francisco, no problem. But here in Minneapolis, it’s just not the norm.”

Sherman says he modeled the menu’s format (and its pricing) on other top-tier, albeit few-in-number, tasting menus in town, such as Demi, Travail and Paris Dining Club. But Owamni’s is on a larger scale than those boutique dining experiences.

“Even Gavin’s only got 20, 30 seats,” he said, referring to Gavin Kaysen’s tasting-menu-only Demi. Owamni seats more than 80, and will have two seatings a night.

On top of scale, there’s another challenge. The kitchen does not cook with “colonial” ingredients that were brought to North America, including cane sugar, wheat flour and dairy. The menu is naturally gluten-free, and easily made vegetarian or vegan upon request.

Creating a decolonized, 13-course fine dining experience is a big flex for Minnesota’s most famous restaurant, one that’s giving Sherman a bit of the jitters.

“We were worried, because it was a risk to change the menu format 100%, and basically create a whole different restaurant concept for a few weeks,” he said.

“But why not?” he added. “It breaks up the monotony.”

His staff, including executive chef Lee Garman, appreciate the shake-up. Other than the smoked bison and the venison tartare, “everything else is pretty new,” said Garman, who came from Los Angeles and has been with the restaurant for a year and a half.

Deciding on the new dishes was collaborative.

“These are things that I’ve been thinking about, or different members of the team have been thinking about for a while, and they’ll bring it up and we’ll test it and maybe run it as a special in some other way. Then we kind of just took those ideas and we’ve been playing with them for the last month and a half,” Garman said.

Sherman is happy to spread the responsibility to up-and-coming chefs. “So many restaurants are just built on the ego of the chef,” he said. “I do get attention all the time, yes, but it’s not about my ego. … I’m trying to share this great creative opportunity with our staff and give people the opportunity to grow.”

The new menu leaves room for change, and guest chefs will stop by to leave their own marks.

“I think it’s important to stretch your legs and sometimes break out of your box,” Sherman said.

So far, the bookings have been coming in, and if there’s enough demand, the new format could extend beyond the first six weeks.

“It’s looking good,” Sherman said. “I feel very positive about this.”

And, now that the restaurant is officially part of Sherman’s culinary education and food relief organization, North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS), the pressure is off to make a profit.

Some seats are earmarked for staff to give away. And for those who still want a casual lunch, there’s NATIFS’ Indigenous Food Lab Market at Midtown Global Market.

Owamni’s new direction is “different,” Sherman said. “I appreciate fine dining, I appreciate the creativity. And I think there’s a lot of positives in fine dining. There’s also a lot of pieces broken around fine dining, too, and we’re just dipping our toe into how we can do things a little bit differently. Just play with it and see what happens.”

Words from the chef

Throughout the two-hour preview of Owamni’s tasting menu, Sherman had plenty to talk about. Here’s his take on:

Fine dining and privilege:

Sherman has dined at some of the top restaurants in the world, including one memorable five-hour lunch that ran for $700.

“I enjoy the artistry. I do enjoy the creativity.” But $700? “It’s just so far from realism. So, we’re just trying to showcase that we can do the same vein of things, and showcase a lot of the artistry.”

But it doesn’t stop there. “We cannot just toot our own horn about it,” Sherman said. “We can really do this with purpose, because these ingredients are pushing this money directly to these producers.”

The long-term impact of Owamni and NATIFS:

Dining at Owamni has always been about more than what’s on the plate. Its parent nonprofit, NATIFS, has a training focus, and much of the kitchen staff have been coached on their jobs “from the ground up” — an opportunity many aspiring Indigenous cooks haven’t had.

Additionally, NATIFS is working to open similar training labs and higher-end restaurants in touristy centers of other communities. The next one is slated for Bozeman, Mont., with Anchorage, Honolulu, Rapid City and Tulsa on the horizon.

From there, the opportunities cascade. More Indigenous restaurants mean more chances for Indigenous producers to sell their products, priming them for bigger contracts, such as the federal government. And that gets healthier food onto reservations and into schools, prisons and other institutions.

“We’re thinking literally 10, 20, 50 years out about these contracts,” Sherman said. “We want to create a system that moves beyond our lifetimes. We can’t fix all the world’s problems, but we can set up the next generation for success as best as we can.”

Owamni pursuing a liquor license:

A wine pairing featuring mostly BIPOC-made wines is available as an add-on to the tasting dinner. So is a zero-proof cocktail pairing that celebrates seasonal ingredients and teas foraged from northern Minnesota. “It’s been a fun challenge” to make mocktails without sugar and fruits that aren’t native to North America, Sherman said.

Eventually, cocktails will become a bigger part of Owamni’s bar program when the restaurant attains a full liquor license, something Sherman is pursuing. When the restaurant opened in 2021, it deliberately did not serve liquor out of sensitivity to Indigenous communities. Sherman wants to make sure the use of liquor has “a lot of intentionality.”

“It should have a purpose and meaning, and not just having Coors Light in neon in the window,” he said.

Owamni

Where: 420 S. 1st St., Mpls., owamni.com On the menu: The Waníyetu menu runs through Valentine’s Day. During that time, Owamni will not have regular lunch or dinner service, and walk-ins will not be accepted. Tickets: The 13-course tasting is $175 and must be booked in advance at Resy. Beverage pairings from BIPOC producers will be available to purchase at the dinner. Go casual: For a more casual dining experience, the Indigenous Food Lab Market at Midtown Global Market serves hot food Monday through Saturday. 920 E. Lake St., Mpls., natifs.org/ifl-market