This acclaimed Minneapolis restaurant is creating inventive zero-proof cocktails using Indigenous ingredients.

by: Audrey Morgan | liquor.com

What does a cocktail program look like without spirits, citrus, or sugar?

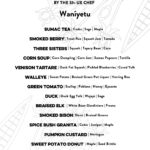

At Owamni, the acclaimed Indigenous restaurant in Minneapolis, the answer might resemble the Dagwaagin, a squash-based shrub that gets its heat from fresh ginger, sweetness from maple syrup, and a boost of acidity from apple cider vinegar. Topped with soda water, it’s one of the most popular drinks on Owamni’s fully Indigenous zero-proof menu.

This spotlight on “decolonized” ingredients has garnered Owamni nonstop accolades since Lakota Sioux chef Sean Sherman opened the restaurant in the summer of 2021. Dishes on the food menu omit non-native ingredients like beef, dairy, and wheat flour to focus on Indigenous produce and game, and the beverage program has been a crucial part of Owamni’s vision since day one.

The restaurant’s original bar director and general manager Kareen Teague, a member of the Ojibwe tribe within the Anishinaabe group, launched an innovative zero-proof cocktail menu without cane sugar and citrus, relying on sweeteners like maple syrup and honey, as well as acid sources that include tart sumac berries. The menu pays homage to Teague’s heritage with ingredients that are native to the area like corn and currants, and Anishanaabe names for each drink.

Teague has since parted ways to work as the bar manager at Dashfire Distillery in Minneapolis, but he maintains a relationship with Owamni, where his sister, Jasmine, is now an integral part of the bar team. Although the decision to focus on zero-proof cocktails partly evolved from the lack of a full liquor license, Jasmine says the non-alcoholic aspect makes sense for the restaurant’s mission.

“We’ve seen firsthand what alcoholism has done to our Indigenous community,” she says. “Kareen really wanted to focus on the medicinal part of [non-alcoholic cocktails] and keep the ingredients Indigenous.”

Many of the menu’s ingredients were part of the siblings’ upbringing on Minnesota’s Red Lake reservation. “We had so many plants and flowers growing up,” says Jasmine. “My mom named me after a flower. Then my dad would work with herbs and use them for a lot of spiritual practices.”

Their family’s ancestral knowledge has been worked into all aspects of the restaurant’s drinks menu.

“I like to make sure that each drink is not just something that is delicious to consume but that it’s providing something for the body as well,” says Jasmine.

Nettle leaf, for example, contains calcium that can help prevent Type 2 diabetes, she says, a prevalent issue in their community, while sage is a diuretic. Both find their way into the Bashkodejiibik (the Anishanaabe word for sage), a drink that also includes bergamot and blackberry. Seasonality dictates the menu as well. Manoomin (wild rice), harvested in the fall, found its way into a horchata-like drink on last year’s winter menu.

Owamni’s bar team works closely with the kitchen to minimize food waste. “That was something I learned early on in our culture, that every part of everything always has a use,” says Jasmine, attributing this knowledge to the Ojibwe tribe’s Seven Grandfather teachings.

Leftover aronia berries from a culinary event, for instance, became the base of the Ziiwiskaagamin, a sour-style drink with cranberries, sumac, balsam fir, and chamomile.

Owamni doesn’t skip alcohol entirely, and offers a wine and beer menu. But like everything at the restaurant, selections are chosen thoughtfully. Sherman has cultivated relationships with wine producers around the world to create a wine selection that’s entirely BIPOC-sourced, featuring Indigenous producers like te Pā, Camins 2 Dreams, and Twisted Cedar, as well as producers of color from Mexico and South Africa.

“Sean wanted to pick a platform in a generally white-dominated space,” says manager Chrissy Sierra.

As with the zero-proof menu, the so-called limitations open up a world of possibilities. “The fun thing about Mexican wines is they have none of the same rules as California or European wines,” says Sierra. As an example, she points to one of her favorite selections, a Grenache-Mourvedre-Carignan blend from Valle de Guadalupe producer Bruma. “There’s no gatekeeping. You can grow whatever you want in whatever region and just see what sticks, what tastes good.”

The bar staff at Owamni continues to grow, and the restaurant was recently acquired by Sherman’s non-profit North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS), which will allow Sherman and his team to expand Owamni’s mission beyond Minneapolis and provide more resources for Indigenous people around the country. It’s a mission that comes through clearly in each thoughtful food and drink item on the menu.

“Part of decolonization is getting back to our roots and relying on nature to heal us,” says Jasmine.